INTRODUCTION

Jack Cunningham - Practice Based PHD

Overview of Cultural Context

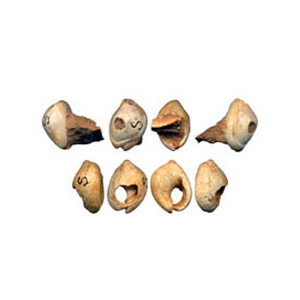

In 2006, a group of perforated marine gastropod shell beads found at the Western Asian site of Skhul in Israel and the North African site of Oued Djebbana in Algeria were dated to the Middle Palaeolithic period, 100,000 to 135,000 years ago. (fig 1.1) The shells from Skhul were found by archaeologists to be part of a layer containing human fossils. Together with the remoteness of these sites from the nearest shorelines, this indicates deliberate transport by humans for symbolic use and demonstrates the earliest recorded emergence of modern human behaviour (Vanhaereny, et al 2006: pp1785 -1788). This predates by 25,000 years, the discovery in 2004 of 39 perforated shell beads dating from the Middle Stone Age (75 thousand years ago), at the Blombos cave site on the shoreline of the Indian Ocean (Henshilwood, et al 2004: 404). With such early origins, these finds position the wearing of jewellery as the oldest of basic human instincts though one can only surmise the power or significance, if any, this bestowed on the wearer at that time.

Artefacts remaining from earliest history show jewellery has been a potent and universal part of human experience. Shells, beads, stones, then metal have been fashioned to adorn the human body to create images of power and status, magic and desire. (Game 2005: xiii).

Jewellery can be understood on a number of different levels; as a means of communicating position, status, rank, of measuring wealth and indicating gender, of conveying sentiment or as a means of simple body decoration. Devoid of any sense of utility it is moreover, capable of bestowing a certain power upon the wearer as in ritualistic or shamanistic ceremony e.g. that used by pre-Columbian Indians, and in ceremonial use, such as royal regalia (more commonly called ‘Crown Jewels’). During the seventeenth century,

Apart from being an object of great price it is a symbol and a sign. It was even more than that at the beginning of the Renaissance when it had been endowed with a quasi-magical power. “Every bishop wears a sapphire in his pastoral ring,” says the Mercure Galant of 1678, “to remind him of his duty to help victims of the plague and cure them by means of the virtue which nature has vested in this precious stone”. (Lanllier & Pini 1983: 40).

The wearing of jewellery has long been an indicator of familial wealth and of celebration in many societies. For example the ornate chest and head decorations worn on special occasions by the women of Marken in the Netherlands, and the significantly heavy chest decorations worn in Estonia, ‘speak’ of the same status as the extravagant headdresses worn currently by the sons and daughters of the Dong people in China’s remote and mountainous provinces of Guangxi, Guizhou and Hunan. (fig 1.2)

The very nature of jewellery and its cultural context is a well-documented subject. For the 1998 exhibition Jewellery Moves, it is adequately defined as a;

...collective noun for a series of relatively small scale objects which can be attached to clothing, or worn directly on the body, for personal adornment. (Game & Goring 1998: 5).

Methodological Considerations

As a practice-based PhD submission, the object is central to this research and is at the heart of each Chapter, connecting aspects of past with current practice, against a backdrop of cultural diversity. The intention of this textual dissertation is to investigate the genre of narrative jewellery. Existing literature comprehensively covers the history of jewellery, its socio-cultural relevance, its design and manufacture, and embraces the contemporary studio jewellery movement as a powerful means of personal and societal expression (Dormer, Drutt English, Turner, Lanllier & Pini). While there is reference to narrative work, further literary analysis indicates no satisfactory interpretation of the narrative genre, and no focused definition of its intention to communicate exists. By scrutinising the author’s work process and personal output, in relation to the work of other contemporary makers, the creative process is thoroughly examined through the finished artefacts. Empirical study forms the basis of this research involving a multi method approach.

In Chapter 1 a constructivist or relativistic approach is used as a research methodology to establish the context and construct of narrative jewellery practice as a genre within the wider framework of contemporary studio output. This relationship is examined in order to extrapolate a clear and succinct definition of contemporary narrative jewellery and the maker’s intention to communicate this narrative to the viewer, through the intervention of the wearer.

The influence of differing value systems is examined in Chapter 2. ‘Meta-analysis’ (Robson 2002: 368) is used in the investigation of cultural behaviour. Through the identification of appropriate global paradigms, the correlation between the creative environment and national characteristics is presented through grounded theory analyses. Differences and commonalities of practice are identified.

Choosing to examine current practice in Europe, Chapter 3 not only locates, for the first time, the significant current trends and preoccupations, but also positions the author’s output within this wider narrative field. Through the various aspects of curating and mounting the largest exhibition of its kind, Maker-Wearer-Viewer, together with the use of questionnaires and organising a one day Symposium, hermeneutics and qualitative analysis are used when identifying and documenting the output of European makers.

Interpretation of creativity and the creative process is largely based on knowledge, experience and observation. Post positivism was not considered appropriate, nor was quantitative analysis, rather, a holistic case study of the author’s practice is presented in Chapter 4. Evaluation through reflective/reflexive practice, together with qualitative analysis is used as methodological tools for external verification of this practice. A number of work process methods are used to generate the artefacts; drawing, writing, digital recording and sourcing, and a variety of technical skills employed during making. Exhibitions are the vehicle used to present this practice, the evidence of the work process, while individuals and focus groups provide evidence of wearer/viewer interaction and interpretation. This will include the trophy designed for the Arts & Business Scottish Awards 2002 and the questionnaire responses from the exhibition Brooching the Subject. This systematic approach elicits objective results which offer new insights into the production of contemporary narrative jewellery and make a genuine contribution to our knowledge and understanding of the field.