Chapter 2 – Defining the Field

The Creative Environment

All individuals have the potential to express artistic behaviour through a variety of diverse activities. ‘Anthropologists have found that art reflects a people’s cultural values and concerns.’ (Haviland 1996: 413). This chapter will look at global paradigms in order to establish a link between those cultural values and the creative individuals engaged in the making of the narrative objects which they reflect. When one examines theories of creative problem solving, many factors contribute to the debate of what constitutes a creative individual and what strategies and techniques may be employed to stimulate creative outcomes. Creativity is about risk taking, making connections and generating new solutions, about ‘…linking these new ideas to restraints, grammars and rules, and of course to reality.’ (Landry & Bianchini 1995: 19). There is considerable knowledge of the cognitive processes at work in creative problem solving which also explores how educators may foster creativity in others, how a creative environment can be nurtured, or how one might quantify a creative act. (e.g. Isaksen et al 1997, Bailin 1994, Ghiselin 1985).

Environmental conditions are a key factor in the development of the individual ‘…cultural anthropologists, neurobiologists and psychologists have amassed a substantial amount of evidence indicating that a universal human nature actually exists.’ (Metcalf 1997: 72). An appropriate and supportive environment or climate, where obstacles are removed, clearly plays an important part in the development of human nature and in our ability to respond creatively as individuals, with defined characteristics such as ‘openness’ and ‘freedom of choice’ (Cole, Sugioka & Yamagata-Lynch 1999: 277). That said, the construct of any given environment, and its impact on creative behaviour, may well mean different things to different people, depending on time, context and place, conversely ‘…are there physical environments that inhibit creativity..?’ (McCoy 2005: 169). The generally accepted premise supports that, in addition to meta-cognitive activity, creativity is a ‘behaviour resulting from the interaction of the person and the environment.’ (Schoenfeldt & Jansen 1997: 73).

In acknowledging the importance of the immediate environment on the creative behaviour of an individual or group, it may therefore be reasonable to suggest that societal factors could also be identified which influence creative outcomes on a larger demographic scale, such as the social history and construct of a city, cultural trends of a population, the politics and education system of a country, the wealth of a nation. McCoy further suggests that, ‘A person’s professional, socio-historical, and domestic circumstances are experienced in distinctive and unique physical environments.’ (McCoy 2005: 187). Eysenck suggests the causes of creative achievement as being a ‘multiplicative function of three variables’, cognitive, environmental and personality (Eysenck 1995: 38). The environmental, referred to as ‘the exterior context’ (Bonneau & Amegan 1999: 209), are factors and politics that directly influence educational policy, popular culture, funding opportunities, etc., and they differ fundamentally from one country to another, and from continent to continent. We may therefore accept Amabile’s statement that ‘creativity is best conceptualised not as a personality trait or as a general ability, but as a behaviour resulting from particular constellations of personal characteristics, cognitive abilities and social environment.’ (Amabile 1983: 358).

The possibility of the existence of universal transcultural human characteristics is a persuasive argument which indicates that, as Bruce Metcalf says, a ‘…pan-cultural human nature’ exists and that there are ‘…a number of behaviours that appear to occur in every known society.’ (Metcalf 1997: 72). As mentioned previously, while the wearing of jewellery may be viewed as a pan-global, basic human instinct, perhaps the creative impulse that generates the jewellery is subject to a more complex range of factors.

There is a danger in making generalised statements about the national characteristics imbued in a contemporary object, particularly in the early Twenty First Century when physical movement from one country, or continent, to another is relatively inexpensive and straight forward. Europeans now move about more freely, and more quickly, than ever before. In addition, through the internet and available technologies, there is ready access to imagery from anywhere in the world, and cross cultural influences can be observed in the way we now eat, dress, decorate our homes, and in speech patterns. This easy mobility has resulted in a creative milieu of trans-national makers ‘…there are Swiss artists living in London; German artists living in Spain; Australian artists in Germany – and so on.’ (Game 2005: xvi). This miscegenation of cultures has, of course, developed over centuries. From its earliest days, London attracted a multicultural population, where Celts mixed with Romans and Saxons with Danes, and we can observe this in many areas of the UK. It was not uncommon for Scottish architects during the Nineteenth Century to journey through Europe and beyond, and we can observe how that experience influenced their creativity in the cities we currently inhabit. There are many reasons for this cultural cross-fertilising; economics, immigration and migration, European Colonialism and the British Commonwealth, the politics affecting the changing face of Europe through the EU, even the spoils of war can explain how objects find themselves displaced from one culture to another, the Benin Bronzes a prime example. Seized by the British from the Royal Palace of the Kingdom of Benin, Nigeria during the expedition of 1897, around 200 of the plaques continue to be housed in the British Museum. Through early trade and smuggling, one can observe on a local level the influences on language, customs and architecture between the east coast villages and ports of Scotland such as Limekilns, Culross and Berwick Upon Tweed and the small ports and towns of the Netherlands, namely Verre and Middleburg. Similarly, one might acknowledge cultural intercourse between Shetland and Norway, or Jersey and France.

Global Paradigms

In order to contextualise the work of European makers, it is apposite to position Europe within a wider framework, against other global paradigms. In so doing, this will identify whether there are traits and similarities, or distinct and unique characteristics. Are we so homogenised that we are in danger of becoming culture bound, unable to see things beyond the culture in which we exist? For instance, is there a recognisable American style or a particular European aesthetic? Are there global trends, or are local issues and values clearly identifiable? Although there is a wealth of literature on the traditional, ethnic and folk-art jewellery of countries such as Africa, Russia and India and the indigenous populations of native American Indians and the Inuit (Eskimo) peoples of North America, there is far less evidence of, or documented material on, an equivalent practice to contemporary studio jewellery. The countries outwith Europe which offer the greatest scope for comparison, are located within the 'developed' world and those with an identifiable contemporary output and similar socio-political status: United States of America, Australia, New Zealand and Japan.

United States of America

With a parallel Arts & Crafts movement similar to the UK the contemporary studio jewellery movement had early origins in the USA. As we move through the early twentieth century narrative jewellery, through makers such as Ramona Solberg, Margaret de Patta and Sam Kramer, consequently found its earliest voice in the United States. (fig 3.1) Contemporary jewellery, or wearable art, gained a respected position in the post war years through exhibitions such as Modern Handmade Jewelry held in 1946 at the influential Museum of Modern Art in New York and subsequent exhibitions mounted at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis during 1948, 1955 and 1959. This early acceptance of craft as a vehicle of middle-class self expression was the culmination of a number of factors. Mainstream manufacturing in the world’s industrialised areas, Scandinavia, Western Europe, Britain and North America had, by and large, caused the demise of the working-class artisan craft worker. Further, ‘The economic structure for this quasi-art has been provided …by art school training, state museums purchasing for collections, the development of applied arts magazines, state grants.’ (Dormer 1998: 139). Due to European turmoil during the 1930’s, most notably the Nazi electoral victory of 1933, an influx of influential European academics moved to the United States. Joseph Albers took up a teaching post at the newly founded Black Mountain College, North Carolina and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy left London to set up the New Bauhaus in 1937. This saw the education system influenced through art colleges such as the Institute of Design in Chicago, Cranbrook Academy of Art in Michigan and later through the Department of Design at Yale University and Cleveland Institute of Art whose graduates include Thomas Gentille and William Harper.

One important factor that would in part account for the early emergence of a narrative aesthetic in the United States stems from their College system. Traditionally, jewellery departments have been placed within fine art schools, as opposed to textiles and fibre art which grew from the domestic, home economics departments. This gave rise to contemporary jewellery in America, more commonly referred to as art jewelry (to give it its American spelling), having an altered status to that of its European counterpart where jewellery has always been a design discipline. The object as a vehicle for narrative art and personal expression was being fully explored by artists such as Joseph Cornell and jewellers would be studying and working alongside the likes of Robert Rauschenberg and Ray Johnson, Johnson himself being a graduate of Black Mountain.

There was a strong desire to ‘explore an entirely new artistic expression and a general trend toward a simpler and less stressful way of life after the trauma of World War II.’ (Greenbaum 1995: 31). During this time crafts were generally supported through public interest, ‘People bought the new craft because they liked it and related to it.’ (Dormer 1998: 140). Dissemination of information, education, exhibitions and contact was made through groups such as the Handcraft Cooperative League of America (1940), which consolidated with the American Handcraft Council in 1942 to form the American Craftsmen’s Cooperative Council. The ACCC publication Crafts Horizon began the same year and in 1943, through a pro-active approach, started an educational programme under the newly founded American Craftsmen’s Educational Council. These two bodies became, in 1979, the American Craft Council and Crafts Horizon is now called American Craft.

The current practice in the USA displays a storytelling narrative that is largely autobiographical in terms of reference, making personal comment the most popular vehicle of expression. There is also a fine line between sculpture and jewellery, simplistically one of scale, which gives rise to the position that American jewellers regard themselves as artists. This easy ability to talk eloquently about themselves through the art of jewellery reflects American society’s confidence in articulating its dominant position on the global stage. They are a nation that regards individual freedom to be of paramount importance, a melting pot of people and immigrant nationalities. Viewed from a European perspective much of American work is visually explicit, the narrative clearly expressed, extravagant, often containing too much information with nothing left to the imagination, ‘…closer to real life than many of their European counterparts.’ (Staal 1990: 10).

There is consequently an abundance of makers to choose from who demonstrate the full spectrum of narrative and in any selection, it is worth noting that this is merely a sample of those working within the genre. Notable examples include the familiar names of; Richard Mawdsley, Bruce Metcalf, William Harper, Kim Overstreet/Robin Kranitzky, Joyce Scott, Judy Onofrio, J. Fred Woell, Keith Lewis, Van LeBus, Keith Lo Bue and Thomas Mann. (fig 3.2) Of these, the works of Harper, Metcalf and Mann offer diversity through their use of materials and approach.

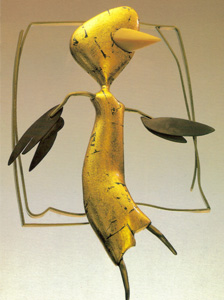

The inclusion of found objects and, in particular, readymades, is predominant in the American aesthetic. Mann’s prodigious studio production of jewellery made exclusively from non precious materials satisfies a market of consumers who identify with his Techno-Romantic assemblages. Techno to represent the technical or technological aspect of our lives, and Romantic the human reflection of our need to acknowledge the impact of that technology. His boxed pieces from the Collage Box & Brooch series, Cat Box and Bird Box Aviatrixdemonstrate the strong influence of Joseph Cornell. The work is light and optimistic in presence, despite its physically large and heavy appearance. (fig 3.3)

With Metcalf, each piece is seen as an ‘autonomous object’, and the person wearing it is simply the site where the work is located. His signature image is that of a figure, an amorphous form, angst ridden and metaphorically searching. (fig 3.4) One is compelled to take the figures seriously despite their semi-abstract, almost caricature appearance. In pieces such as Learning to Build and Wood Pin series, there is a story in progress which the viewer has interrupted but feels the need to bring to a conclusion despite the ambiguous imagery. Indeed Metcalf invites us to surmise as to the narrative content, ‘…I do not insist that the intended narrative be the only interpretation. People are free to make up whatever story they choose when they see these works.’ (Metcalf 1993: 92).

Like Metcalf, Harper’s work is also figurative. These are seductive pieces incorporating brightly coloured vitreous enamel and found objects, but with a dark narrative subtext that owes much to his interests in anthropology, iconography, religious symbolism and primitive art. Mostly brooches and fibulas, his early pieces flirt with the notion of the senses, with touch, sound and even smell playing a part in a number of different series such as Freudian Toys, Rattle and Hair Fetish. The viewer makes these connections through ‘...a labyrinth of associations and meanings revealed through color, material and form.’ (Manhart 1989: 8). There is great richness in the diverse use of materials. In addition to the strong drawing of his cloisonné enamelling, shells, pearls, and precious stones are juxtaposed against base materials such as hair, teeth, claws and snake rattles. Harper’s interest in the duality of beauty versus ugliness, the concept of opposites, manifests itself through this inclusion of insects, rodent parts and snails. (fig 3.5)The subject matter of European religious imagery, Saint Sebastian, Saint Augustine, Saint Anthony, the pain and ecstasy of Martyrs, forms the basis of a number of portraits and self portraits. Manhart continues, ‘These objects seem to be voodoo dolls with which the artist is tortured’, his Migraine series a narrative channel conveying his own personal pain. (Manhart 1989:17).

Another factor that may account for a difference between the work of European and American jewellers also occurs during art college training. European tradition places a great emphasis on the way ideas are developed through the process of repeated drawing on paper. Design solutions are generated slowly through the process of synthesis, of divergence and resolution, before reaching the bench at which point construction and fabrication begins. The output of European jewellery is perhaps more conceptual and issue-based as a consequence. The American approach is much more hands on with little preliminary drawing or designing, of having an idea and going with it, creating through spontaneity and energy. There are pros and cons with each educational system. There is weakness in assuming the first idea to be the best, and only, idea, yet strength in capturing the essence of an idea as and when it happens, as opposed to the tradition of laboured designing that fails to capture the moment and the immediacy of working directly with materials, but which hones each idea in a considered manner to generate the best possible resolution.

Australia and New Zealand

Current practice in Australia and New Zealand (Aotearoa) is often characterised by a narrative centred on personal and social comment. This is particularly the case in New Zealand where traditional skills and an empathy with the environment are inherent characteristics, and where the choice of materials is of paramount importance among contemporary jewellers, a practice still in its relative infancy. Natural materials such as bone, fibre, shell and stone, reference indigenous people and contribute to the cultural imagery of a Polynesian society.

These materials…are used holistically. They are not used in the European tradition as additive elements and decorative appendages on a framework of metal. Here they are the structure and their natural forms are a strong imperative in this jewellery. (Edgar 1989: 52).

Migration from the tropical islands of East Polynesia began over a thousand years ago. Over the centuries, with a coastline rich in shellfish such as paua, the seas providing whalebone and ivory from many species, the ancient timbers from the primeval forests, and the diverse geological formations produced quantities and of high quality pounamu (nephrite jade), ‘Styles of carving changed to express the mythologies and genealogies of people in a new land.’ (Edgar 1989: 49).

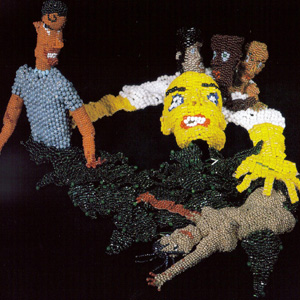

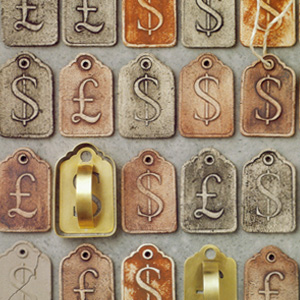

Thoughtful and insightful discussion around issues of Maori and South Pacific culture is at the heart of work by makers such as Areta Wilkinson, Alan Preston, Paul Annear, Elena Gee, Michael Couper, Hamish Campbell and, most notably, Warwick Freeman. Areta Wilkinson, whose signature motif is the identity tag or tie-on label ‘…reflects on cultural identity. Her ancestry is traced through Maori and pakeha (non-Polynesian) culture, and she creates a series of pendants out of shell, bone and other traditional materials which examine identity.’ (Game & Goring 1998: 55). On wearing a piece, one becomes an exhibit, a participant in the cataloguing of cultures or artefacts. (fig 3.6) In one group of pieces titled Not for Sale, the tags are embossed with £ and $ signs, giving these works a wider socio-political context. So too, her group of brooches in the 05 Series explores materials associated with Maori body adornment, incorporating rare feathers, totara and flax.

Campbell’s work utilises bone, carved into images of fish, birds, animals and hybrid mythical characters. His output is, aesthetically, the most overtly illustrative of traditional indigenous Maori folklore in New Zealand. A piece titled Hunted, Hunter references the sea and its importance in the life of its people. (fig 3.7)

Warwick Freeman incorporates a selection of materials such as shell, jade, bone and jasper into his brooches and pendants. Although not given to describing the meaning of his own work, rather allowing the owner and viewer to interpret its content, his references embrace the mythology and aesthetic of Maori and South Pacific culture. Speaking on the subject of those who own and wear a piece of Warwick Freeman jewellery, Julie Ewington says,

Ownership is a relationship compounded of desire, responsibility, dependence. Initially the object spoke loudly, commanded a degree of commitment. Ever after it is at the mercy of personal whim and the vicissitudes of social change, of circumstances not entirely controlled by any player in the daily dramas of life. Jewellery is a go-between, the visible token of affection between people, the marker of certain significances and understandings. (Ewington 1995: 2). (fig 3.8)

The four pointed South Pacific star is a constant and more recently, ‘Freeman uses universal symbols: the heart, the star, the flower, fashioned from traditional New Zealand materials…to create brooches which are simultaneously familiar and strange and highlight questions of cultural identity.’ (Game & Goring 1998: 55).

In parallel with New Zealand, an Australian vernacular has grown from the influence of indigenous materials and traditional craft techniques, together with design styles and influences brought to the country during the early period of European settlement of the late 18th Century. During the 19th Century, this meshing of style/technique/materials continued to influence the design direction of Australian objects. Moving into the 20th Century, Robert Bell of the National Gallery of Australia observes, ‘Craft training, within the growing field of technical education, began to offer a more professional approach to the production of functional and decorative objects and advance the use of an Australian idiom in design.’ (Bell 2006: 1). Set up in the 1970s, Craft Australia together with lively educational programmes, saw increased activity across the contemporary craft spectrum. Bell continues, ‘The flowering of Australian studio crafts in the period from about 1965 to 1985 was not planned, but it progressed with committed and timely support from Government funding agencies and craft organisations.’

The narrative genre has been explored for many years by Pierre Cavalan in Sydney, and by Sue Lorraine and Catherine Truman of the well established Gray Street Workshop in Adelaide. Among a younger generation of makers, Melinda Young and Francine Haywood stand out, both jewellers exploring issues of femininity. Haywood uses metaphor for her matriarchal role by casting everyday kitchen utensils from toilet paper. With titles such as Slither, Scum and Fanny, Young produces provocative brooches cast from the small end pieces of used bars of soap.

Cultural identity is explored by Cavalan, a French jeweller now living in Australia. His colourful and confident brooch and neckpiece assemblages take on the appearance of medals, rosettes and garlands, as though presented on behalf of a nation or city to a most important visitor or awarded for some special act. (fig 3.9) They appear as though the contents of a button box have been emptied and re-arranged into a radial or mirror image symmetrical pattern. However, to suggest that there is anything random or haphazard about these works is to belie the skill of Cavalan as a designer. ‘These pieces are more than simply reconstructions or assemblages, they are magical transformations of past fragments each with their own story which transmute into a fresh, coherent entity.’ (Anderson 1998: 63). A brooch titled Rainbow Warrior Medal has a strong political commentary based on the sinking of the Greenpeace ship in Auckland harbour. The brooch titled Mourning Gloriesis constructed from found objects, badges, semi-precious stones, bits of old costume jewellery, a cast cherub and skeleton, and depict two photographic images of, one surmises, young Australian soldiers presumed deceased. Cavalan’s style has an international transferability, for although his references are by and large Australian, he has a gift for collecting and incorporating relevant objets trouvé when exhibiting on other continents.

Although becoming more common in the UK, shared workshops such as Ipso Facto in Sydney, Mari Funaki and Marianne Hosking in Melbourne and Fingers Collective in Auckland, established a collective infrastructure whereby Australian and New Zealand makers were able to meet, share facilities and equipment and provided a unique opportunity for creative exchange. Among these, the Gray Street Workshop in Adelaide has been at the forefront of this concept. It is now over twenty years old and during this time has developed and grown intellectually, moved location several times, impacted on the development of the Jam Factory, and over this period its four partners have remained constant. Along with Julie Blyfield and Leslie Matthews, Sue Lorraine and Catherine Truman have produced work that has helped define Australian contemporary jewellery. In the past Lorraine’s work has been related to the female body, the hands, the heart, anatomical drawings, with imagery of the house and heart, the one mutating into the other, used as metaphors for ‘…probing the banalities and constraints of ordinary domestic life.’ (Anderson 1998: 116) (fig 3.10a, fig 3.10b)

Catherine Truman’s work also makes reference to women’s issues using imagery of fish and the lifeboat as metaphor for mortality, fertility, and isolation. More recent work is a series titled Invisible Places to Be and concentrates on the relationship she has with her own body. (fig 3.11) The carved pieces suggest sinew, bone, ligament and express movement and contortion. They are at one and the same time, beautiful and almost painful.

Japan

Although the wearing of jewellery was not entirely uncommon, Japan has no particular historical tradition in the field of jewellery as it was not an aspect that formed a part of the country’s social culture or dress code. It is more likely, as Simon Fraser observes, that items of jewellery existed within society as ‘…the result of trading during periods when Japan was open to outside influence and ideas.’ (Fraser 2002: 9). Japanese opinion of Western jewellery is observed in a letter written by an attendant of a Japanese delegation to the United States in 1860. Published in an American newspaper it shows how negative the response to jewellery was at that time, ‘They (American women) have pierced their ears like the women in many barbarian countries and put gold or silver decorations…barbarised by such foolish customs.’ (Seki 2005: 219). Indeed sumptuary edicts prohibited the wearing of gold and silver except on armour, swords or official robes, excluding most of the population, especially women, from wearing precious metal. The use of highly decorative artefacts such as hair combs, the inro, tsuba and netsuke, were objects that served a particular purpose or function, and obfuscated the need for superfluous decoration in the form of jewellery. Tsuba and netsuke were sometimes decorated with narrative imagery, figures from mythological or religious stories. Particularly in the 19th Century, the peaceful Tokugawa era allowed the development of more flamboyant designs which chokin artisans in the cities produced for the nouveau riche tradespeople.

The UR Accessory Association was established in 1956 (changed to the UR Jewellery Association in 1963), the organisation named after the ancient city of UR in Mesopotamia. Excavations here, had revealed magnificent examples of gold metal work dating to 4000 BC, and became the benchmark of the groups manifesto to produce work of the highest quality. The change of the groups name was strategic and reflected an important shift in perception,

The change from “accessory” to “jewellery” was made in appreciation of the concept the latter carries in Europe where jewellery is an independent field in formative art. In taking in jewellery from Europe, the Japanese artists also imported the accompanying concept. (Hida 1995: 20).

The group continues today and has not altered its particular interest in metal working and precious gems. Some of the early UR exhibitions had narrative themes such as Fairy Tale or Kojiki (the story of the Japanese birth myth). These early exhibitions contained a lot of figurative work telling stories that resonate with the earlier themes depicted on the tsuba.

The Japan Jewellery Designers Association (JJDA) was begun in 1964 by Yasuhiko Hishida and has been presided over by such eminent makers as Yasuki Hiramatsu and Reiko Yamada. In the early years the JJDA played a pivotal role in the process of giving contemporary work a forum and voice through annual member exhibitions and publications. In contextualising Japan’s post-war economic position however, an exhibition intended to convey the energy of Japan’s post-war modern crafts movement titled: Crafts in Everyday Life in the 1950’s and 1960’s, was held in 1995 at the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo. It showed no jewellery at all from that period. Crafts were regarded as part of Japan’s strategy for economic growth and were closely linked with industrial design through the core activities of ceramics, glass and wood, rather than fashion and its accessory, jewellery. Although contemporary jewellery manufacture was firmly established and clearly documented as an activity, its visibility was somewhat obscured (almost literally), through public opinion, and to a degree, the politics of the day. The JJDA was instrumental in raising the profile of contemporary work during the 1960s, by making the significant decision to refrain from calling their work an accessory (soshingu) to fashion, and established it as an independent activity of artistic merit. Exhibitions of Western jewellery contributed to this cultural shift, such as the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths exhibition in 1965 at the Wako department store in Ginza, Tokyo and that mounted by Americans Olaf Skoogfors, Stanley Lechtzin and Miye Mitsukata at the Odakyu department store in Tokyo in 1968.

Just prior to the mounting of Crafts in Everyday Life in 1995 the seminal exhibition, Contemporary Jewellery – Exploration by Thirty Japanese Artists, was also mounted at the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo. It was the first exhibition of its kind and scale, either in or outside Japan, and presented a comprehensive overview of the contemporary scene.

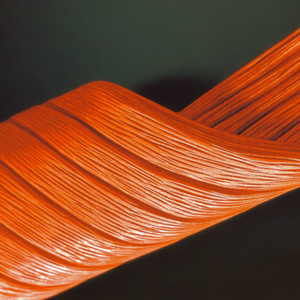

With such a short history in this field Japan has no cultural ‘baggage’, making it a fascinating country to observe. With the demise of its traditional dress codes, designers are free to experiment with the endless possibilities of body decoration. There is consequently a freshness and naivety about much Japanese work. There are also the exquisite materials and extraordinary skills, still largely unknown in the West, that offer a unique opportunity to the new generation of Japanese jewellers. Rather than being constrained by technical knowledge the opportunity exists to explore, with complete freedom and openness, the potential offered through the synergy of ideas, materials and techniques. Techniques such as raising and forging on air (traditional hammering), metal carving (chôkin), alloying (shakudo, shibuichi and mokumegane), inlay and lacquer work (urushi) and Japanese paper (washi), which can be observed in the work of contemporary makers such as Mizuko Yamada, Haruyoshi Yamashita, Sakurako Matsushima and Kimiaki Kageyama. Continued growth in the subject is secured by the JJDA and institutions such as Hiko Mizuno College of Jewelry in Tokyo and the highly regarded Tokyo Geidai (Tokyo National University of Fine Arts and Music), which are at the forefront of Universities that allow students to specialise in contemporary studio jewellery whilst continuing the practice of traditional techniques.

With a particular interest in Japanese culture, I have participated in group shows and held solo exhibitions in Kyoto (A Sense of Place - Gallery Gallery 1997) and Tokyo (On the Line – Arai Atelier Gallery 2004). My understanding of Japanese education and culture comes through interaction during lectures and workshops delivered there, contact with the British Council and British Embassy, and my observation of contemporary practice during annual visits to the country since 1997. Contemporary jewellery is now varied and eclectic in its design and is always underpinned by complete mastery of materials and techniques. That said there is an aesthetic commonality that runs through much of the work, an emotional sensitivity described by makers in terms of ‘rhythm’, ‘transformation’ of ‘free expression’, that ‘appeals to all the five senses’. Work that I may have suggested was outwith the narrative genre, based on for example traditional Japanese hammering techniques, form or texture, and are here described as powerful expressions of emotion. For example Mizuko Yamada’s strong hollow forms are described ‘Its grand curves and eye-catching form…manifest maternal love and a powerful life.’ (Takagi 1995: 162).

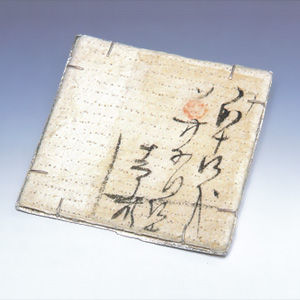

In one sense much of Japanese work is narrative. Seldom making obvious social or political comment (perhaps reflecting societal conformity) or adopting external references, it speaks from an inner cognition, reflective and philosophical ‘…most Japanese do feel that Japanese art has a tendency to capture human situations through instinct and inspiration rather than logic and theory.’ (Hida 2001: 25). The narrative, for a Westerner, is therefore neither obvious nor instant, rather it is subtle and poetic, making it much harder to access as a viewer coming from a society with such different codes and traditions. We may, for example, enjoy the qualities of Japanese paper but it is a different matter to empathise with its quiet spiritual presence and inherent values. Speaking of his ‘washi’ pieces the respected Tokyo Geidai Professor says, ‘My aim is to create forms with force and grace, which are built to bring materials’ possibilities into full play. I am also concerned about whether my work means anything to our life.’ (Hiramatsu 1995: 120).

Most overtly narrative is the works of Yukio Obi, Kyoko Fukuchi and Sae Yoshizawa, each reflecting elements of traditional cultural reference. Yoshizawa’s work encapsulates photographic images of the three dimensional world we live in, the sky or environment, and through manipulation of the two dimensional printed photographic paper she re-creates three dimensional forms through the technique of folded origami. (fig 3.12) The rings in particular become a vehicle for Yoshizawa to evoke her feelings of affinity with the scenery, ‘grasping a piece of sky or clouds and keeping it in my pocket. For me, inspiration always lies in ordinary spaces, within myself and my everyday life.’ (Yoshizawa 2001: 120).

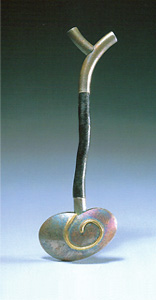

The work of Yukio Obi is centred on the Shinto shrine. (fig 3.13) The shoulder ornaments and pendants are flamboyant and complex pieces containing depth and layers of religious significance, ‘Obi’s unique ideas incorporate these primitive Japanese concepts of mother nature teamed with religious sentiment.’ (Takagi 1995: 164).

Kyoko Fukuchi also works with paper, traditional ‘washi’ sourced from antique ledgers of her family’s drapery business. There is a literal and metaphorical narrative present in her work, ‘My great-grandfather wrote these words in ink 100 years ago. They are like memory flowing through my body…my fingers are in direct contact with the paper and my thoughts are transmitted directly into it.’ (Fukuchi 2001: 45). (fig 3.14)

Japanese familial hierarchy and social conformity dictates a strong work ethic and the need for young family members to acquire knowledge through scholarly study and research. British Council figures show that large numbers of Japanese students are currently studying in the UK, and that Art & Design subjects are overwhelmingly the most popular. As a destination, the UK is the second most popular after the USA and statistically ahead of Australia, the significance of this being that we shall inevitably observe the influence of Western education, and culture, on the design and manufacture of Japanese work in the future, and this cultural milieu works both ways. This paradigm has already been witnessed in the work of Korean jewellers who have previously undertaken undergraduate and postgraduate study in the USA and Europe, notable examples being Jung-Hoo Kim and Eun-Mee Chung. (fig 3.15) Given the previous comment on ‘easy mobility’, a cautionary note is struck by Amanda Game,

This internationalism, this moving between cultures can be exciting and stimulating for an artist. And yet, there is always the danger that the work itself, by nature of its very eclecticism, can become an expression of a sort of bland internationalism in style and content: rootless and ultimately fruitless. (Game 1997: 14).

This deflection is carefully avoided by Chung who references her own cultural heritage through the use of Sottae, a symbolic, shamanic object emphasising her narrative on gender issues and themes of love and hate.

In his 1985 exhibition National Characteristics in Design for the Boilerhouse Project at the V&A Museum, the curator Stephen Bailey examined and compared the products from nations including America, Italy, France, Britain, Germany and Japan. Bailey felt there was an increasing temptation to believe that all industrialised products look the same, but argued that this view was largely unfounded and that products have clear visual indicators of their national character almost to the extent of cultural stereotyping. ‘Miniaturisation was a key to Japan’s success in the export market…’ not as a result of the development of the microchip Bailey suggests, ‘Far from it. The bonsai tree and the art of origami had long since given the world some idea of the Japanese flair for miniaturisation and ingenuity.’ When talking of automotive design, Bailey describes the American yellow checker cabs, transit authority buses and American locomotive design, ‘American design bears all the hallmarks of New World confidence – big, brash, dynamic’, ‘astonishingly muscular’, ‘aggressive’, ‘unlike any European counterparts.’ In referencing the English as being misguided or not, he suggests they desire evidence of craftsmanship in their products and an association with pseudo-aristocratic status, highlighting as an example the Giles Gilbert Scott telephone boxes as ‘…miniature exercises in classical architecture, each topped off with a copy of the Regency architect, John Soames favourite, shallow pendentive dome.’ (Bailey 1985: pp1-10).

‘Many anthropologists believe national character theories are based on unscientific and over-generalised data. Others have chosen to focus on the core values promoted in particular societies.’ (Haviland 1996: 146). Anthropologists hold diametrically opposing views as to whether a national character exists. I believe the examples discussed in this chapter fully support with my position that national characteristics can be observed through the ‘core value’ of creative behaviour and the narratology of objects.

The fact is artistic behaviour is far from unimportant and is as basic to human beings as talking. Moreover, it is not simply 'artists' who do this; for example, all human beings adorn their bodies in certain ways and by doing so make a statement about who they are, both as individuals and as a member of social groups of various sorts. (Haviland 1996: 414).

Further, this Chapter has highlighted how the identity of the culture to which we belong, its rituals and conventions, its politics and history, the fabric of our lives within the larger cultural community in which we function (whether temporarily or permanently), does indeed influence creativity. It manifests itself through the objects that speak of the people who create and use them.